- 摘要

- 背景

- 女性原生阴道微生物组

- 乳酸杆菌在控制阴道病原菌中的潜力

- 乳酸杆菌表面活性分子(Surface-Associated Molecules,SAMs)的潜力

- 肽聚糖(Peptidoglycan,PG)

- 脂壁酸(Lipoteichoic Acid,LTA)

- 细菌多糖

- 生物表面活性剂(BS)

- 乳酸杆菌SAMs应用的挑战

- 结论

摘要

人类阴道被多样化的微生物组定殖,这些微生物包括正常的细菌组和真菌组。乳酸杆菌是从健康人类阴道中最常分离到的微生物,主要包括卷曲乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus crispatus)、加氏乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus gasseri)、阴道乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus iners)和詹氏乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus jensenii)。这些阴道乳酸杆菌被认为能通过抑制病原体的数量来防止其定植。然而,阴道生态系统的破坏会导致病原体过度生长,从而引发复杂的阴道感染,如细菌性阴道病(BV)、性传播感染(STIs)和外阴阴道念珠菌病(VVC)。诱发因素如月经、妊娠、性行为、抗生素滥用和阴道冲洗等,都可能改变微生物组结构。因此,阴道微生物组的组成在决定阴道健康中扮演重要角色。由于乳酸杆菌被广泛认为是安全的(GRAS),它们作为传统抗菌治疗的替代或补充方案,已用于预防和治疗慢性阴道炎并重建阴道生态平衡。此外,乳酸杆菌长期给药的预防效果也得到充分验证。本综述旨在强调乳酸杆菌衍生物(即表面活性分子)在开发阴道感染疗法中的有益作用,包括抗生物膜、抗氧化、抑制病原体和免疫调节活性,并讨论将其推广至人类健康应用面临的挑战。我们希望为开发乳酸杆菌衍生物作为阴道健康中传统益生菌疗法的补充或替代提供参考。

关键词: 阴道微生物组、阴道生态系统、益生菌、乳酸杆菌、乳酸杆菌衍生物、表面活性分子

背景

人类微生物组计划(HMP)和整合人类微生物组计划(iHMP)由美国国立卫生研究院(NIH)资助,是跨学科项目,旨在解析肠道、阴道、口腔和皮肤部位的微生物组组成和宏基因组特征[1, 2]。这些项目的发现对于建立微生物组变化与疾病机制之间的联系,以及识别诊断生物标志物具有重要意义[3, 4]。

人类阴道微生物组包含多样的有益微生物和机会性病原体,这些微生物共存于阴道环境中[5, 6]。为深入研究阴道微生物组,已开发多种“-组学”技术,包括PCR-变性梯度凝胶电泳(PCR-DGGE)、DNA焦磷酸测序、荧光原位杂交(FISH)、定量PCR和微阵列[7]。此外,代谢组学、宏基因组学、宏转录组学和蛋白质组学等现代技术也被用于揭示微生物组的功能活动[8],通过整合微生物与代谢图谱,可解码微生物群落在调节人体健康中的作用[8]。迄今,16S rRNA基因测序是识别复杂微生物组的主要方法,可推断导致疾病的微生物群落特征[9]。技术进步后,Ravel等人利用高通量测序鉴定出五种阴道细菌群落类型[10]。这些研究表明,阴道微生物组与宿主处于共生状态[11],真菌(尤其是念珠菌属)也作为共生菌存在于阴道黏液层,与细菌共同构成复杂的生态系统[12, 13]。生育年龄女性的阴道菌组会随荷尔蒙、年龄、性行为和抗菌药使用等因素波动[14–17];菌组失调则可导致机会性病原体过度生长,进而引发疾病[18]。

阴道菌组失调反映微生物组结构破坏,常与多种妇科疾病相关,包括BV、VVC、STIs(滴虫病、HPV感染、沙眼衣原体感染、HIV易感性、生殖器疱疹)等[19–23]。失调的显著特征之一是阴道 pH 值升高——由于乳酸减少,BV、CT 和 VVC 患者的阴道 pH 显著高于健康女性[24]。若不干预,微生物组失调还可能导致流产、早产和受孕率降低等严重后果[25]。因此,维持阴道微生物组平衡对健康至关重要。

人类微生物组知识的进展推动了活体生物疗法的发展[26]。粪便微生物组移植(FMT)已在复发性难辨梭菌感染中成功应用[27];类似地,阴道微生物组移植(VMT)有望治疗难治性阴道感染。首例 VMT 报道在复发性 BV 患者中重建了乳酸杆菌主导的微生物组,且未见不良反应[28]。此外,乳酸杆菌联合抗生素治疗复发性 BV 的倾向性明显降低[29]。在另一项研究中,甲硝唑联合鼠李糖乳杆菌 (L. rhamnosus GR-1) 和罗伊氏乳杆菌 (L. reuteri RC-14) 治愈率达 88%,而单用甲硝唑仅为 40%[30]。这些益效部分归因于乳酸杆菌表面活性分子(SAMs),如肽聚糖(PG)、脂磷壁酸(LTA)、生物表面活性剂(BS)和胞外多糖(EPS)[31, 32],它们可拮抗Candida albicans、Staphylococcus aureus、Streptococcus mutans、Escherichia coli、Pseudomonas aeruginosa、Salmonella typhimurium等多种病原体[33–35]。因此,深入了解乳酸杆菌及其衍生物(SAMs)有助于开发针对阴道菌组失调的新疗法。

过去十年间,阴道微生物组研究呈爆发式增长,揭示了女性阴道菌组多样性及其在健康与疾病状态下的差异[10, 24, 36–38]。以乳酸杆菌为主的菌组常见于健康阴道,而疾病状态下阴道 pH 上升、菌组多样性增加。部分女性阴道菌组动态变化显著,受到多种宿主诱因影响。至今,阴道菌组失调的根本原因尚不明确。本综述旨在概览健康女性阴道的微生物组与真菌组组成,并强调乳酸杆菌及其衍生物(SAMs)在控制阴道病原体、促进阴道健康中的潜在作用。

女性原生阴道微生物组

健康阴道以乳酸杆菌主导,真菌仅处于边缘存在[39]。有益细菌与宿主共生,通过保护阴道环境免受病原体干扰,宿主则为其提供营养[11]。乳酸杆菌的定殖是健康阴道微生物组的重要特征,主要种类包括卷曲乳酸杆菌 (L. crispatus)、加氏乳酸杆菌 (L. gasseri)、阴道乳酸杆菌 (L. iners) 和詹氏乳酸杆菌 (L. jensenii)[10, 40, 41]。阴道菌组会在不同生命阶段(婴儿期、青春期、妊娠、更年期)发生变化[42],而荷尔蒙、抗生素、月经和阴道冲洗是常见影响因素[6, 43, 44]。

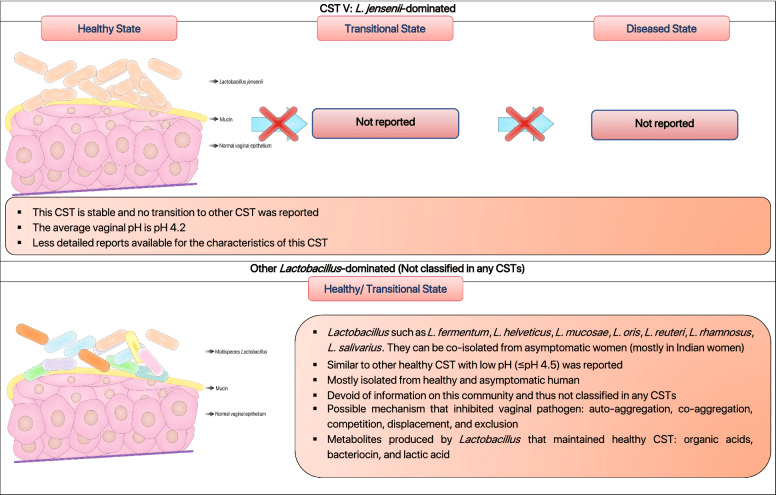

健康阴道的主要乳酸杆菌丰度决定了细菌群落类型,称为群落状态类型(CSTs)[10]。CST I–V 分别由L. crispatus、L. gasseri、L. iners、多种乳酸杆菌和BV 相关厌氧菌混合主导,以及L. jensenii 主导(见图 1)[6, 10]。其中 CST I、III 和 IV 研究较多、也最常见,CST II 和 V 较罕见[45, 46]。DiGiulio 等[47]与 van de Wijgert 等[46]均在健康女性中报告了 CST II 和 V 的存在。Gajer 等人进一步将 CST IV 分为 IV-A 和 IV-B:IV-A 中除L. iners外,还含杆菌属(Corynebacterium)、精细球菌属(Finegoldia)、链球菌属(Streptococcus)或厌氧球菌属(Anaerococcus);IV-B 则富含 BV 相关细菌[6]。

图 1 假想示意:阴道群落状态类型(CST I–V)及其主导菌种

根据已有科学文献,人类阴道群落状态类型(CSTs)可分为五种常见类型,分别对应健康或疾病状态下微生物群的不同特征。各CST由以下优势菌种主导:卷曲乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus crispatus)、加氏乳杆菌(Lactobacillus gasseri)、阴道乳杆菌(Lactobacillus iners)、细菌性阴道病相关菌群(BVAB)以及詹氏乳杆菌(Lactobacillus jensenii)[6, 10, 47, 96, 262, 263]。

阴道中乳酸杆菌的存在协调了一种独特的炎症模式,促成了不同的群落状态类型(CSTs)。值得注意的是,CST III 和 CST IV 中阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 的存在与较高的促炎因子基线水平相关,如巨噬细胞迁移抑制因子(MIF)、白细胞介素‑1α、白细胞介素‑18 和肿瘤坏死因子‑α(TNF‑α),这些因子负责激活阴道中的炎症反应 [48]。以卷曲乳酸杆菌 [Lactobacillus crispatus] 主导的阴道微生物群(CST I)始终与健康阴道相关,而以阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 主导的阴道环境(CST III)更容易发生阴道菌群失调(图 1) [49, 50]。多项研究表明,卷曲乳酸杆菌 [L. crispatus] 对性传播感染(STIs)、细菌性阴道病(BV)和外阴阴道念珠菌病(VVC)的保护作用,与其产生乳酸和细菌素以维持阴道健康状态的能力密切相关 [51, 52]。与此同时,阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 缺乏必需氨基酸合成能力,迫使其严重依赖宿主提供的外源氨基酸 [53]。其有限的代谢能力和对宿主营养的依赖,使其对环境变化高度敏感 [53]。此外,它还产生一种独特的乳酸异构体(L‑乳酸),这种形式不足以在阴道感染期间抑制病原菌的扩增 [54, 55]。另外,大量研究显示,人类阴道微生物群的组成因个体而异,并受到激素(如怀孕和月经)以及种族的显著影响 [10, 56]。激素,尤其是雌二醇的影响,事实上可以刺激 CST I(以卷曲乳酸杆菌 [L. crispatus] 主导)向 CST III(以阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 主导)或混合乳酸杆菌群落的转变,但很少转向病态的阴道群落(图 1) [6, 46]。此外,病态群落(CST IV)和促进 BV 状态的群落(CST III)在撒哈拉以南非洲地区更为常见 [6, 10]。可以推测,这些人群的遗传因素可能改变阴道免疫反应,从而有利于阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 及引起菌群失调的病原共生菌定殖 [56, 57]。如前所述,对阴道微生物群落特性的研究极大地扩展了我们对健康与病态阴道微生物群之间关系的认识。在阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 基因组中发现的前噬菌体表明,噬菌体可能影响乳酸杆菌在阴道生态系统中的适应策略和丰度 [58]。因此,未来需进一步研究以阐明乳酸杆菌噬菌体的存在及其对健康与病态阴道的贡献。

大多数亚洲和白人女性的核心阴道微生物群分别由 80.2% 和 89.7% 的乳酸杆菌主导 [10]。相比之下,乳酸杆菌并非黑人和西班牙裔女性阴道微生物群中的唯一优势属(分别仅占 59.6% 和 61.9%) [10]。一项针对 151 名女性(65 名 HPV 阳性,86 名 HPV 阴性)的横断面研究显示,HPV 与厌氧菌(如多形拟杆菌 [Bacteroides plebeius]、卢豆单胞菌 [Acinetobacter lwoffii] 和口腔普雷沃氏菌 [Prevotella buccae])的高丰度显著相关 [59]。这一发现表明,阴道微生物群多样性增加会显著提高 HPV 感染风险 [59]。可以推测,阴道微生物群的破坏可能影响宿主对 HPV 感染的先天免疫,从而导致宫颈癌发生 [60]。此外,Lee 等人 [61] 也揭示,阴道菌群失调与 HPV 感染密切相关。HPV 感染女性的阴道微生物群中普雷沃氏菌 [Prevotella]、血链球菌属 [Sneathia]、双杆菌属 [Dialister] 和杆菌属 [Bacillus] 的丰度较高,而乳酸杆菌丰度低于健康女性 [61]。另外,以乳酸杆菌低丰度和阴道加德纳菌 [G. vaginalis] 主导为特征的阴道菌群失调,与 HPV 感染及宫颈肿瘤发展显著相关 [62]。此外,乳酸杆菌低丰度以及阴道中加德纳菌 [Gardnerella]、布鲁氏菌 [Brucella]、血链球菌属 [Sneathia] 和其他杂菌的高比例,在 HPV 和生殖器疣感染患者中更为常见 [63]。总之,阴道微生物群失调与 HPV 相关感染的风险密切相关。简而言之,针对阴道菌群失调的干预治疗可能降低 HPV 感染和宫颈癌发展的风险 [64]。

与阴道微生物群分析相比,人类阴道真菌群仍未得到充分研究。针对阴道真菌群的首个高通量测序由 Drell 及其同事于 2013 年完成 [39]。根据 Drell 等人 [39] 的研究,从健康爱沙尼亚女性中鉴定出 196 个真菌操作分类单元(OTUs);最优势的门为子囊菌门(Ascomycota,58.0%),其次是未指定真菌 OTUs(39.0%)和担子菌门(Basidiomycota,3.0%)。子囊菌门中最常见的 OTUs(Saccharomycetales)是念珠菌属(Candida,37.0%),主要包括白色念珠菌 [C. albicans](34.1%)、克鲁斯念珠菌 [C. krusei](2.3%)、营养念珠菌 [C. alimentaria](该研究中标为 Candida sp. VI04616,0.3%)、近平滑念珠菌 [C. parapsilosis](0.3%)和都柏林念珠菌 [C. dubliniensis](0.04%) [39]。类似研究也表明,念珠菌群落无症状存在于健康女性中 [65, 66]。此外,Ward 等人 [67] 报道,无论分娩方式如何,婴儿的主要真菌群与母亲阴道真菌种类相同(白色念珠菌 [C. albicans]) [67]。婴儿中白色念珠菌 [C. albicans] 的定殖可通过母婴垂直传播显现 [68]。总之,这些发现表明,白色念珠菌 [C. albicans] 可以在不引起症状性感染的情况下定殖于阴道。同时,越来越多研究强调一些风险因素,如激素水平、糖尿病、口交、阴道冲洗、滥用抗真菌药和抗生素、宫内节育器使用及会阴撕裂,这些因素与 VVC 发病显著相关 [69–71]。关于阴道相关感染的人类微生物群研究选定文献汇总见表 1。

表1 列出了有关阴道相关感染的人类微生物群研究的代表性文献。

| 国家/地区 | 研究设计 | 主要发现 | 参考文献 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 比利时蒂嫩 | 26名女性:11名健康、5名BV、7名VVC、3名BV‑VVC年龄:23‑40横断面研究使用PCR‑变性梯度凝胶电泳(PCR‑DGGE)和16S rRNA实时PCR分析进行微生物分析 | PCR‑DGGE显示健康女性的阴道微生物群随时间稳定,以嗜酸乳杆菌 [L. acidophilus]、加氏乳杆菌 [L. gasseri]、阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 和阴道乳酸杆菌 [L. vaginalis] 为主导;少量阴道加德纳菌 [G. vaginalis] 与乳酸杆菌共存于一些健康女性中,可能作为“哨兵”物种,对环境、生物和物理变化敏感;BV患者报告乳酸杆菌丰度低,同时BV相关细菌(如阴道加德纳菌 [G. vaginalis]、阴道阿托博菌 [A. vaginae]、钩端螺旋体 [Leptotrichia]、大球菌属 [Megasphaera]、普雷沃氏菌 [Prevotella]、葡萄球菌属 [Staphylococcus]、链球菌属 [Streptococcus]、韦荣氏菌属 [Veillonella])增加;VVC患者中非H₂O₂产生的阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 增加,嗜酸乳杆菌 [L. acidophilus]、加氏乳杆菌 [L. gasseri] 和阴道乳酸杆菌 [L. vaginalis] 丰度减少 | [264] |

| 美国爱荷华州 | 横断面研究42名女性:21名健康、21名RVVC(2年内≥4次)年龄:18‑40使用16S rRNA末端限制片段多态性(T‑RFLP)进行微生物分析 | VVC感染女性与健康女性在细菌群落和阴道pH值上无显著差异;大多数RVVC患者无症状;未发现阴道群落构成与RVVC风险的关联性 | [265] |

| 美国乔治亚州 & 马里兰州 | 横断面研究396名非孕妇年龄:12‑45使用条码16S rRNA测序进行微生物分析 | 提出五种阴道CST(I、II、III、IV、V)以根据乳酸杆菌丰度分析阴道微生物群状态;黑人和西班牙裔女性阴道pH较高(pH 4.7‑5.5),相比亚洲和白人女性(pH 4.2‑4.4);CST III(以阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 主导)和CST IV(以BVAB主导)在黑人和西班牙裔女性中更常见 | [10] |

| 中国 | 95名非孕妇:30名健康、39名VVC、16名BV‑VVC、10名BV横断面研究使用条码16S rRNA测序进行微生物分析 | 健康中国女性阴道微生物群以乳酸杆菌为主,阴道pH呈酸性(< 4.5);BV感染女性微生物多样性最高(乳酸杆菌丰度低);BV‑VVC女性呈独特模式,乳酸杆菌丰度较高;单纯VVC女性微生物群多样,唑类治疗后出现链球菌 [Streptococcus] 和阴道加德纳菌 [Gardnerella] 主导的异常群落;BV‑VVC女性抗菌治疗后乳酸杆菌丰度增加 | [266] |

| 爱沙尼亚 | 494名健康无症状白人女性年龄:15‑44横断面研究使用条码16S rRNA进行细菌分析,ITS测序进行真菌分析 | 健康无症状女性阴道微生物群以乳酸杆菌为主;部分女性报告BVAB(如阴道阿托博菌 [A. vaginae]、阴道加德纳菌 [G. vaginalis]),可归为无症状BV;阴道微生物多样性随pH升高及异味分泌物增多;念珠菌属,尤其白色念珠菌 [C. albicans],仍是无症状女性最常分离酵母菌 | [39] |

| 美国西雅图 | 45名女性参与纵向研究(2007‑2010)甲硝唑治疗:7、14、21、28天使用16S rRNA qPCR和数学建模分析细菌动态 | 治疗第1天BVAB快速减少,在过渡期阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 丰度逐步上升;治疗对阴道加德纳菌 [G. vaginalis] 无效,BV复发率高 | [267] |

| 加拿大多伦多 | 182名孕妇(孕11‑16周)与先前310名非孕加拿大女性比较微生物谱使用通用引物 cpn60测序进行分析 | 以乳酸杆菌为主的CST孕妇比非孕妇乳酸杆菌丰度更高;孕妇报告更低丰富度与多样性(Mollicutes和乌氏支原体 [Ureaplasma]丰度低),与早产和流产风险降低相关;激素诱导的糖原生成可能为阴道细菌生长创造有利环境,解释孕妇细菌负荷更高 | [268] |

| 肯尼亚/南非/卢旺达 | 80名女性参与阴道生物标志物研究:40名健康、40名BV8周纵向(5次随访)革兰氏染色、qPCR、宫颈阴道冲洗液中免疫介质定量 | 79%健康女性群落由卷曲乳杆菌 [L. crispatus] 主导并伴有阴道乳酸杆菌 [L. vaginalis],詹氏乳杆菌 [L. jensenii] 和加氏乳杆菌 [L. gasseri] 未检出;健康妇女以阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 主导,其微生物多样性和炎症与性活动及闭经相关;BV感染女性乳酸杆菌丰度低,阴道加德纳菌 [G. vaginalis]、阴道阿托博菌 [A. vaginae] 和双歧普雷沃氏菌 [P. bivia] 丰度高,伴促炎细胞因子(IL‑1β、IL‑12)升高和抗蛋白酶 elafin(IP‑10)降低 | [269] |

| 美国马里兰大学 | 40名非孕妇横断面研究使用16S rRNA测序分析微生物阴道溶血素(细胞毒蛋白)定量 | CST IV女性阴道溶血素浓度高于CST I(高乳酸杆菌丰度)女性;CST III(阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 主导)女性中等水平;缺乏乳酸杆菌群落女性阴道加德纳菌 [G. vaginalis] 丰度高,与pH、Nugent评分及溶血素浓度升高相关 | [270] |

| 土耳其伊斯坦布尔 | 28名健康白人女性:14名子宫内膜异位症患者、14名健康前瞻性观察性队列研究使用16S rRNA宏基因组测序 | 无论子宫内膜异位症与否,乳酸杆菌皆为优势属;异位症患者阴道加德纳菌 [G. vaginalis] 丰度显著高于健康组;异位症患者阴道及宫颈无阴道阿托博菌 [A. vaginae],宫颈中大肠杆菌 [E. coli]、志贺氏菌 [Shigella]、链球菌 [Streptococcus] 和乌氏支原体 [Ureaplasma] 丰度增加 | [271] |

| 美国马里兰大学公共卫生学院 | 39名女性:26名HPV阳性(14名高危型)、13名HPV阴性横断面研究16S rRNA测序分析微生物,液相色谱‑质谱法分析阴道代谢物 | HPV阳性女性生物胺(腐胺、乙醇胺)水平高,谷胱甘肽(GSH)、糖原和磷脂水平低;CST III HPV+女性生物胺和糖原相关代谢物高;CST IV HPV+女性GSH、糖原和磷脂代谢物高;HPV+女性在各CST中氨基、脂类和肽类浓度均低于HPV–;高生物胺和GSH所致氧化应激环境或损害宿主抗感染反应 | [272] |

| 意大利博洛尼亚 | 79名女性:21名健康、20名BV、20名CT、18名VVC横断面研究16S rRNA MiSeq测序分析微生物,¹H‑NMR进行代谢组学分析 | 健康女性群落以卷曲乳杆菌 [L. crispatus] 主导;CT患者乳酸杆菌丰度低,阴道阿托博菌 [A. vaginae]、粪杆菌属 [Faecalibacterium]、大球菌属 [Megasphaera]、罗斯氏菌属 [Roseburia] 丰度高;BV/VVC患者乳酸杆菌低、BVAB高;失调条件下二甲胺减少、三甲胺增加;健康女性产乳酸与支链氨基酸(缬氨酸、亮氨酸、异亮氨酸)多;BV患者生物胺和短链有机酸增加;VVC患者葡萄糖水平高,或减少卷曲乳杆菌丰度并促进念珠菌毒力 | [24] |

| 美国密苏里州(圣路易斯) | 255名女性:42名假丝酵母定植和255名:42名念珠菌定殖、213名非念珠菌定殖含黑人和白人女性,正常、中度及BV微生物群巢式横断面研究使用16S rRNA qPCR分析微生物乳酸杆菌对白色念珠菌体外抑制测试 | 20%(52/255)、39%(99/255)和38%(98/255)的女性分别为卷曲乳杆菌 [L. crispatus]、阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 和非乳酸杆菌主导;阴道乳杆菌主导群更易定殖念珠菌;卷曲乳杆菌上清液pH较低(乳酸浓度高),较阴道乳杆菌上清更有效抑制念珠菌 | [273] |

| 卢旺达基加利 | 68名高危BV或TV患者:55名主动就诊7天口服甲硝唑(500 mg)使用16S rRNA HiSeq测序和BactQuant qPCR分析 | 甲硝唑后BV治愈率54.5%;BVAB丰度中度下降(16.4%患者群落减少≥50%);乳酸杆菌总丰度上升,以阴道乳杆菌 [L. iners] 丰度最高;高丰度病原共生菌及阴道加德纳菌与治疗失败相关,或因生物膜形成 | [274] |

- BV:细菌性阴道病(Bacterial Vaginosis)

- CT:沙眼衣原体感染(Chlamydia trachomatis)

- RVVC:复发性外阴阴道念珠菌病(Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis)

- VVC:外阴阴道念珠菌病(Vulvovaginal Candidiasis)

- TV:阴道毛滴虫(Trichomonas vaginalis)

- BV–VVC:BV 与 VVC 共感染

- BVAB:BV 相关细菌(BV-associated Bacteria)

- CSTs:群落状态类型(Community State Types)

- IP‑10:干扰素‑γ诱导蛋白‑10(化学趋化因子)

- ITS:内部转录间隔区(Internal Transcribed Spacer)

- OTUs:操作性分类单元(Operational Taxonomic Units)

- PTB:早产(Preterm Birth)

- T1D:1 型糖尿病(Type I Diabetes)

白色念珠菌(Candida albicans)

白色念珠菌(Candida albicans)是阴道的主要定殖者,常从外阴阴道念珠菌病(VVC)感染女性中分离出来【72, 73】。外阴阴道念珠菌病终其一生至少影响 75% 的女性【72】,而首次 VVC 发作的女性中约有 5–10% 会发展成复发性外阴阴道念珠菌病(RVVC,每年 ≥ 4 次发作)【74】。作为阴道中最常见的居民之一,白色念珠菌(C. albicans)经常被证实与乳酸杆菌共同定殖于阴道【75】。此外,非白色念珠菌(NCAC)物种,如热带念珠菌(Candida tropicalis)、光滑念珠菌(C. glabrata)、克鲁斯念珠菌(C. krusei)、都柏林念珠菌(C. dubliniensis)和平滑念珠菌(C. parapsilosis),也常在 RVVC 感染女性中被观察到【76–79】。VVC 和 RVVC 患者报告的非特异性症状包括外阴红斑、瘙痒、性交疼痛、灼热感、白色块状分泌物和酸痛【72, 80】。虽然 VVC 不危及生命,但未解决的 VVC 会影响患者的生活质量,例如心理健康、社交生活、性关系和工作生活【74, 81】。

白色念珠菌(Candida albicans)是一种多形性酵母菌,能在有利条件下从酵母形态转变为菌丝形态【82, 83】。关于白色念珠菌如何从单纯定殖者转变为病原菌的合理解释包括阴道菌群失调、毒力因子表达(如菌丝和生物膜形成)以及分泌天门冬氨酸蛋白酶(SAPs)等蛋白水解酶,这些都会导致阴道免疫毒性【84】。Swidsinski 等人证明,VVC 患者的上皮内病变中含有白色念珠菌(C. albicans)菌丝,并伴随阴道加德纳菌(Gardnerella vaginalis)和阴道乳杆菌(Lactobacillus iners)的共同入侵【85】。这是最有力的证据之一,表明白色念珠菌的形态可塑性(从酵母到菌丝的形成)以及 BV 相关细菌(BVAB)的存在可能共同促成症状性 VVC。此外,阴道微生物群的破坏(如乳酸杆菌数量减少)可能促进念珠菌属物种入侵阴道上皮细胞的能力【18】。在突破阴道上皮细胞后,白色念珠菌的假菌丝和菌丝通过级联激活诱导上皮细胞的 NLRP3 炎症小体,最终引发严重的阴道炎症【86】。在所有阴道微生物群和真菌群研究中,白色念珠菌(C. albicans)仍是 VVC 最常描述的致病因子【87】。VVC 的显著特征是由念珠菌属物种引起的阴道菌群失调和阴道黏膜炎症【85】。此外,阴道真菌群的变化已被证明与糖尿病、妊娠、免疫缺陷、过敏性鼻炎和复发性外阴阴道念珠菌病(RVVC)状态相关【88, 89】。正如后文讨论的,微生物群与真菌群的相互作用可能通过它们之间的短暂或持续协同作用,促进女性 VVC 的发展。探索这些相互作用并寻找潜在的微生物干预措施,对于预防和治疗女性 VVC 至关重要。

细菌性阴道病(BV)

细菌性阴道病(BV)是育龄妇女中最常见的阴道炎症,其特征是阴道微生物群组成从以乳酸杆菌为主转变为多微生物群落【24, 90】。根据 Peebles 等人的研究,全球 23–29% 的女性感染 BV,给每年带来 37 亿–61 亿美元的巨大经济负担【91】。BV 可通过 Amsel 标准、革兰氏染色、Nugent 评分和分子检测进行诊断【40, 92】。它通常伴随大量阴道加德纳菌(G. vaginalis)、普雷沃氏菌属(Prevotella)、阴道阿托波菌(Atopobium vaginae)、血链球菌属(Sneathia)等 BVAB 的过度生长,这正是由于阴道微生物群失调所致【93, 94】。BV 常与 HIV 感染、流产、盆腔炎性疾病、早产、产后子宫内膜炎及性传播感染(STIs)获得的风险升高相关【90, 95–97】。此外,BV 对女性的心理社会造成显著压力;Bilardi 等人证明,复发性 BV 女性常在日常生活中体验到尴尬、自卑和挫折感【98】。

可以设想,乳酸杆菌产生的细菌素和乳酸抑制了阴道中 BVAB 的过度增殖【99】。然而,当阴道菌群失调发生时,以乳酸杆菌为主的微生物群被G. vaginalis及其他 BVAB 取代【100】。近期研究表明,BVAB(如G. vaginalis和A. vaginae)之间的协同作用显著加剧了 BV 的严重性,增加了细菌负担【101, 102】。BV 的另一个重要特征是由G. vaginalis 主导的多微生物生物膜形成,而其他共栖 BVAB 则增强了该生物膜的厚度【85, 103–105】。多项研究还表明,与乳酸杆菌数量减少相关的 BV 阴道微生物群,会增加其他 STIs 的发病率【106–108】。Cone 推断,以乳酸杆菌为主的群落通过强酸化阴道环境和降低炎症细胞因子,减少了 STIs 的传播【109】。多项研究一致表明,乳酸杆菌的存在能通过乳酸显著降低沙眼衣原体(Chlamydia trachomatis)的毒力【54, 110, 111】。

性传播感染(STIs)

性传播感染(STIs),如衣原体感染(Chlamydia trachomatis)、淋病(淋病奈瑟氏菌 Neisseria gonorrhoeae)、滴虫病(阴道滴虫 Trichomonas vaginalis)和梅毒(苍白螺旋体 Treponema pallidum),常引发女性宫颈炎、尿道炎、阴道炎和生殖器溃疡【112–114】。据世界卫生组织(WHO)估计,全球每年 STIs 新发 3.764 亿例,其中衣原体感染 1.272 亿例、淋病 8,690 万例、梅毒 630 万例、滴虫病 1.56 亿例【112】。通常,STIs 可通过短期抗生素治愈,但若不及时治疗,可传染他人并导致流行【115】。这些 STIs 还与宫颈癌、不孕、早产和盆腔炎性疾病的高风险相关【114, 116, 117】。多项研究一致表明,破坏的或 BV 相关的阴道微生物群(乳酸杆菌丰度低)会增加 STIs 的发病率【106–108, 118–120】。此外,STIs 与 HIV 感染风险升高相关:Galvin 和 Cohen 指出,STIs 会破坏阴道黏膜层和免疫稳态,增加 HIV 入侵机会【121】。同时,无症状的衣原体感染常被漏诊【122】。以乳酸杆菌为主的平衡阴道群落,能通过调节阴道上皮增殖和 D-乳酸产生,减少沙眼衣原体入侵上皮细胞【54】。这些研究强调了阴道稳态在提供天然屏障、抵御感染中的关键作用。

尿路感染(UTIs)

阴道也是女性尿路感染(UTIs)致病菌的储存库【123】。引起 UTIs 的常见病原菌包括大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)、肺炎克雷伯菌(Klebsiella pneumoniae)、表皮葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus epidermidis)、B 组链球菌(Streptococcus agalactiae)、粪肠球菌(Enterococcus faecalis)、奇异变形杆菌(Proteus mirabilis)和绿脓杆菌(Pseudomonas aeruginosa)【124–126】。虽然 UTIs 可通过抗生素治愈,但严重并发症(如肾盂肾炎、血尿和慢性肾病)可导致永久性肾损伤【127, 128】。研究表明,诸如G. vaginalis、Prevotella 和 Ureaplasma 等阴道病原菌,可由阴道经尿道上行至膀胱引发 UTIs【129–131】。与以乳酸杆菌为主的健康群落相比,阴道菌群失调会增加 UTIs 获得风险【123, 132】。事实上,小鼠实验中,阴道暴露于G. vaginalis 会引发由E. coli 引起的复发性 UTIs【133】。因此,维持阴道稳态可抑制尿路致病菌上行感染。

中毒性休克综合征(TSS)

另一种严重威胁育龄妇女健康的疾病是中毒性休克综合征(TSS),与阴道中金黄色葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus aureus)产生的 TSS 毒素(TSST-1)相关【134】。已知 TSST-1 在中性 pH(约 6.5–7.0)条件下产生,而这种 pH 常见于疾病状态的阴道【135】。多项研究表明,月经杯、卫生棉条和避孕隔膜的使用会扰乱以乳酸杆菌为主的群落,促进* S. aureus* 生长及 TSST-1 产生【136–138】。TSST-1 过量可导致严重并发症,如器官衰竭、全身炎症甚至死亡【139】。总之,阴道菌群失调不仅削弱了乳酸杆菌的保护作用,也增加了上行致病菌和毒素产生的风险,最终可能导致 TSS。

阴道微生物群的平衡与失调

平衡良好和破坏的阴道微生物群分别对应健康与疾病状态。除宿主易感性与遗传因素外,菌群破坏也直接剥夺了乳酸杆菌对阴道病原菌的保护。未来研究需涵盖更多人群与地理多样性,并整合多组学方法,以开发诊断菌群失调的预测性生物标志物;同时,探索基于益生菌乳酸杆菌或其衍生物(如表面活性分子)的生物疗法,以恢复健康群落、降低 BV、VVC、STIs 等阴道感染的风险。

乳酸杆菌在控制阴道病原菌中的潜力

乳酸菌是一类多样细菌的代表性微生物,其特征为革兰氏阳性、微需氧、耐酸、不产孢子并能产生乳酸 [140, 141]。用作益生菌的主要乳酸菌属包括乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus)、双歧杆菌(Bifidobacterium)、链球菌(Streptococcus)、肠球菌(Enterococcus)和片球菌(Pediococcus) [142, 143]。美国食品药品监督管理局(FDA)授予乳酸的普遍认为安全(GRAS)地位,使其在食品、乳制品和制药行业中得到广泛应用 [144, 145]。例如,德氏乳杆菌保加利亚亚种(Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus)与嗜热链球菌(Streptococcus thermophilus)一起被用作制造酸奶和奶酪的发酵剂 [146, 147]。根据Reid等人,适量给予益生菌乳酸杆菌能够通过恢复微生物和宿主免疫稳态为宿主带来健康益处 [148]。

越来越多的研究阐明了乳酸杆菌对胃肠道、口腔、阴道和表皮层中病原菌的基本益生菌效应 [149–152]。嗜酸乳杆菌(Lactobacillus acidophilus)KS400已被证明通过发酵产生细菌素,抑制泌尿生殖道病原菌如阴道加德纳菌(G. vaginalis)、无乳链球菌(S. agalactiae)和绿脓杆菌(P. aeruginosa)的生长 [153]。此外,来自阴道的鼠李糖乳杆菌(L. rhamnosus)(Lactocin 160)的细菌素能够通过破坏病原菌的化学渗透势在阴道加德纳菌(G. vaginalis)的细胞膜上产生瞬时孔隙 [154]。多项研究还表明,好氧性阴道炎(AV)引起的病原菌,如大肠杆菌(E. coli)、粪肠球菌(E. faecalis)、金黄色葡萄球菌(S. aureus)、表皮葡萄球菌(S. epidermidis)和无乳链球菌(S. agalactiae),通常驻留在阴道中并诱发炎症性阴道炎 [155, 156]。长期使用抗菌药物治疗阴道炎可能导致耐药性的发生 [157, 158]。因此,基于益生菌乳酸杆菌的方法作为传统抗菌治疗的替代方案正在被广泛研究。根据Bertuccini等人 [159],鼠李糖乳杆菌(L. rhamnosus)HN001和嗜酸乳杆菌(L. acidophilus)GLA-14能够显著抑制阴道加德纳菌(G. vaginalis)、阴道阿托波菌(A. vaginae)、金黄色葡萄球菌(S. aureus)和大肠杆菌(E. coli)的生长。为了阐明乳酸杆菌引入阴道微生物群的效果,一项研究表明,口服混合嗜酸乳杆菌(L. acidophilus)La-14和鼠李糖乳杆菌(L. rhamnosus)HN001从第7天和第14天开始显著增加了阴道中鼠李糖乳杆菌和嗜酸乳杆菌的丰度 [160]。在一项类似研究中,口服给予益生菌配方(嗜酸乳杆菌 L. acidophilus PBS066 和罗伊氏乳杆菌 L. reuteri PBS072)以及(植物乳杆菌 L. plantarum PBS067、鼠李糖乳杆菌 L. rhamnosus PBS070 和乳双歧杆菌 B. lactis PBS075)与安慰剂对照组相比,从第7天开始显著增加了阴道中乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌的丰度 [161]。除此之外,还报道多种乳酸杆菌菌株的培养上清液通过抑制黏附和菌丝相关基因的表达显著抑制了白色念珠菌(C. albicans) [162]。讽刺的是,与SAPs相关的基因未受影响,因此表明这些蛋白酶在乳酸杆菌主导的阴道中白色念珠菌生存的重要性。观察到的抗念珠菌活性部分归因于细菌素、过氧化氢和乳酸的存在 [162]。此外,Li等人指出,卷曲乳杆菌(L. crispatus)和德氏乳杆菌(L. delbrueckii)在VVC Sprague‑Dawley大鼠模型中与未治疗对照组相比,能够抑制60–70%的白色念珠菌(C. albicans) [163]。

乳酸杆菌干预已被证明在与抗菌药物联合治疗和预防复发性感染中是有益的。采用这种方法的一项研究表明,口服多种乳酸杆菌(发酵乳杆菌 L. fermentum 57A、加氏乳杆菌 L. gasseri 57C 和植物乳杆菌 L. plantarum 57B)与甲硝唑联合给药,显著延长了BV(51%)和AV(71%)的复发时间,并维持了阴道pH的酸性 [164]。人们认为,耐胆汁酸的乳酸杆菌能够在迁移到阴道腔之前增加肠道中乳酸杆菌的丰度 [148, 165]。然而,口服益生菌如何迁移并在阴道中占主导地位的确切机制仍存在争议 [166, 167]。阴道内给予益生菌也被开发用于恢复破坏的阴道微生物群。Bohbot等人 [168] 报导,28天阴道内给予冻干的卷曲乳杆菌(L. crispatus)IP 174178能够降低复发率(20.5%),并与安慰剂对照组相比延长了BV复发的时间(28%)。此外,含有发酵乳杆菌(L. fermentum)LF15和植物乳杆菌(L. plantarum)LP01的阴道片剂通过抑制阴道加德纳菌(G. vaginalis),恢复了阴道pH的酸性和Nugent评分低于7的阈值(平衡的阴道微生物群) [169]。鼠李糖乳杆菌(L. rhamnosus)BMX 54也已在BV患者中进行临床测试,显示在三个月给药后能够将阴道微生物群恢复到平衡状态 [170]。此外,鼠李糖乳杆菌(L. rhamnosus)BMX 54还显示其作为辅助治疗的潜力,在6至9个月的治疗后重塑阴道微生物群并减少BV复发 [171]。近期证据表明,间歇性应用阴道胶囊(含有嗜酸乳杆菌 L. acidophilus W70、短乳杆菌 L. brevis W63、瑞士乳杆菌 L. helveticus W74、植物乳杆菌 L. plantarum W21、唾液乳杆菌 L. salivarius W24 和双歧双歧杆菌 Bifidobacterium bifidum W28)恢复了以乳酸杆菌为主的阴道微生物群,并与未治疗对照组(每人年10.18)相比显著降低了BV发病风险2.8倍 [172]。同时,使用乳酸杆菌还可以降低VVC复发率。例如,口服克霉唑和含有嗜酸乳杆菌(L. acidophilus)GLA‑14和鼠李糖乳杆菌(L. rhamnosus)HN001以及牛乳铁蛋白RCX的口服胶囊联合给药,与非乳酸杆菌给药对照组相比,在三个月和六个月时分别显著降低了VVC复发率58.4%和70.8% [173]。恢复阴道微生物群对于预防各种阴道感染及其复发率至关重要。根据Xie等人 [174],与传统药物治疗相比,仅使用益生菌对抗VVC和BV的证据不足以推荐。

以乳酸杆菌为主的健康阴道生态系统有潜力保护宿主免受HIV和STIs的侵害 [20, 175]。根据McClelland等人,高丰度的BVAB与女性HIV感染风险相关 [108],可能是由于阴道pH值升高和产生抑制抗HIV免疫的酶 [176]。多项研究已进行体外和离体试验,以确定乳酸杆菌在抑制BV相关细菌和HIV传播的潜力 [177, 178]。从阴道分离的乳酸杆菌菌株产生的培养上清液已被证明能够抑制人类宫颈阴道组织中的HIV‑1型感染 [178]。在这项研究中,乳酸杆菌培养上清液被证明具有杀病毒作用,有助于减少宿主中病毒颗粒的传播 [178]。此外,加热杀死的加氏乳杆菌(L. gasseri)也对TZM-bl细胞系上的HIV‑1株X4感染性表现出高抑制活性(81.5%) [179]。在一项类似研究中,干酪乳杆菌(L. casei)393(1×10⁴细胞/毫升)在30分钟共孵育后能够抑制HIV‑1伪病毒(AD8、DH12和LA1),抑制范围为60–70% [180]。最近,Palomino等人发现,乳酸杆菌对HIV‑1感染的抑制作用与细胞外囊泡的存在相关,这些囊泡抑制HIV黏附和病毒进入目标细胞 [181]。前瞻性研究一致表明,破坏的阴道微生物群增加了女性HIV感染的风险 [23]。未来研究应优先阐明阴道菌群失调与HIV感染的机制,并发现益生菌乳酸杆菌作为HIV预防的有效干预措施。

总体而言,乳酸杆菌在预防阴道感染(如BV和VVC)方面显示出令人期待的效果。使用益生菌乳酸杆菌来纠正阴道微生物群失衡的补充方法迫切需要,以减少抗菌药物的使用。应进行更多关于益生菌乳酸杆菌对抗阴道感染效果的临床试验,以解决益生菌效果的异质性。

乳酸杆菌表面活性分子(Surface-Associated Molecules,SAMs)的潜力

大量研究表明,乳酸杆菌的益生菌效应可能通过竞争定殖、调节宿主免疫反应、促进有益菌交叉喂养,以及产生乳糖酶、胆盐水解酶、有机酸和抗菌化合物等机制实现 [182, 183]。SAMs 是介导宿主-乳酸杆菌相互作用的关键因子 [184]。已报道支持益生菌作用的 SAMs 包括肽聚糖(Peptidoglycan,PG)、细菌多糖、生物表面活性剂(BS)和壁酸(Teichoic Acid,TA) [185, 186]。

乳酸杆菌的核心 SAMs 还包括脂壁酸、多糖、表面层相关蛋白(SLAPs)、黏蛋白结合蛋白(MUBs)和纤维连接蛋白结合蛋白等,这些分子通过与上皮细胞和黏膜层上的模式识别受体直接相互作用,调节宿主生理反应 [187]。这些核心表面相关分子(SAMs)在乳酸杆菌黏附时调节宿主–微生物相互作用。事实上,已有研究证明,SAMs 可通过直接黏附于上皮细胞和黏膜层上的模式识别受体(Pattern Recognition Receptors,PRRs),直接介导宿主的生理反应 [187]。由于乳酸杆菌衍生的 SAMs 在调控阴道内宿主–微生物相互作用方面可能具有重要作用,应进一步聚焦此类 SAMs 的研究,以开发新型基于 SAMs 的治疗方法,作为当前可用疗法的潜在替代方案。

肽聚糖(Peptidoglycan,PG)

肽聚糖(PG)是一种生物高分子,由糖链构成,通过 N‑乙酰葡糖胺(GlcNAc)和 N‑乙酰胞壁酸(MurNAc)侧链交联,形成革兰氏阳性细菌(如乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌)细胞壁的主要结构 [188, 189]。在乳酸杆菌中,PG 网络通常与壁酸(Teichoic Acid,TA)、S 层蛋白及其他多糖共同构成细胞外包膜 [189, 190]。

一般而言,某些性传播病原体(如淋病奈瑟菌 Neisseria gonorrhoeae)能通过抑制宿主产生白细胞介素‑12(Interleukin‑12,IL‑12),减弱 Th1 型适应性免疫反应 [191]。针对这一机制,研究者尝试在小鼠阴道内局部给药微囊化 IL‑12,以逆转免疫抑制并促进病原体清除 [191]。与此同时,乳酸杆菌来源的 PG 表现出卓越的免疫调节功能,可增强宿主的先天免疫反应。例如,干酪乳杆菌(Lactobacillus casei)PG 能通过激活 Toll 样受体 2(TLR2)和核苷酸结合寡聚化域 2(NOD2),诱导小鼠腹腔巨噬细胞分泌 IL‑12 [192];植物乳杆菌(Lactobacillus plantarum)CAU1055 的 PG 则可通过抑制一氧化氮合酶(iNOS)、环氧合酶‑2(COX‑2)及促炎细胞因子 TNF‑α 和 IL‑6,缓解 RAW 264.7 小鼠巨噬细胞中 LPS 诱导的炎症反应 [193]。类似地,嗜酸乳杆菌(Lactobacillus acidophilus)衍生的 PG 在 LPS 刺激的 RAW 264.7 细胞中也显著降低 iNOS 和 COX‑2 水平 [194]。

此外,阴道分离的卷曲乳杆菌(Lactobacillus crispatus)PG 能刺激朗格汉斯细胞(一种阴道黏膜中的树突状细胞)表达 CD207,并显著降低 HIV 入侵受体的表达 [195]。维持阴道上皮和黏膜环境中微生物群与免疫系统的平衡,对预防感染至关重要 [196]。除了免疫调节活性外,短乳杆菌(Lactobacillus brevis)PG 还表现出对生殖器单纯疱疹病毒‑2 型(HSV‑2)的强抗病毒作用,其活性不受热或蛋白酶处理影响,且以浓度依赖方式显著抑制 HSV‑2 复制 [197]。

脂壁酸(Lipoteichoic Acid,LTA)

在许多乳酸杆菌中,PG 分子常与壁酸(TA)或脂壁酸(LTA)共同存在 [198]。LTA 由甘油磷酸重复单元聚合而成,并锚定于细胞膜 [199, 200]。与其他 SAMs 协同作用,LTA 通过调节宿主的模式识别受体及其下游信号通路,参与乳酸杆菌的益生和抗病原效应 [185]。

消除阴道内的多菌种生物膜是预防细菌性阴道病(BV)的重要策略 [201]。研究表明,植物乳杆菌(Lactobacillus plantarum)LTA 可通过抑制蔗糖分解,干扰变形链球菌(Streptococcus mutans)在羟基磷灰石表面的生物膜形成 [35];同株 LTA 亦能显著抑制粪肠球菌(Enterococcus faecalis)在牙本质切片上的生物膜生成及预形成生物膜 [202],提示其在预防和治疗粪肠球菌相关感染中的潜力。此外,LTA 对由放线菌(Actinomyces naeslundii)、唾液乳杆菌(Lactobacillus salivarius)、粪肠球菌和变形链球菌(Streptococcus mutans)共生形成的多菌种生物膜也具有抑制作用 [203]。

除抗生物膜外,乳酸杆菌 LTA 还具有免疫调节作用。例如,约氏乳杆菌(Lactobacillus johnsonii)La1 和嗜酸乳杆菌 La10 的 LTA,可在 LPS 或革兰阴性菌刺激下,缓解肠上皮细胞中过度分泌 TNF‑α、IL‑8 等促炎细胞因子 [204];植物乳杆菌 K8 的 LTA 亦能在 THP‑1 细胞中调节 TNF‑α 和 IL‑10 水平 [205]。BV 及性传播疾病患者常见促炎因子过度表达和中性粒细胞募集,乳酸杆菌 LTA 的免疫调节功能有助于减轻病原菌引起的阴道炎症 [119, 206]。

细菌多糖

细菌在细胞表面形成紧密连接的聚合物,并将其释放到环境中作为胞外多糖(Exopolysaccharides,EPS)(松散未附着的黏液) [31, 207]。通过利用表面多糖模拟宿主的糖结构,病原菌能够在定殖期间逃避免疫系统的监视 [208]。一般来说,菌体分泌的 EPS 对宿主–微生物相互作用中的黏附和细胞识别至关重要 [209]。胞外多糖是高分子量、可生物降解的碳水化合物聚合物,根据其单糖成分可分为同多糖或杂多糖 [综述见 [210–212]]。过去十年中,乳酸菌的 EPS 因其能够抑制蜡样芽孢杆菌(Bacillus cereus)产生的细菌毒素而受到广泛关注 [213]。乳酸杆菌 EPS 的产量受发酵期间培养条件和营养成分的调控 [214, 215]。例如,与酿酒酵母(Saccharomyces cerevisiae)共同发酵 48 小时后,鼠李糖乳杆菌(Lactobacillus rhamnosus)EPS 产量显著增加 40–50%,这与 EPS 基因簇表达上调以及氨基酸生物合成、碳水化合物代谢和脂肪酸代谢增强相关 [216]。此外,五碳乳杆菌(Lactobacillus pentosus)EPS 的产量受到不同碳源的强烈影响,例如葡萄糖可提高 EPS 黏度,从而在奶制品生产中具有更好的增稠效果 [217]。类似研究还报告,在补充葡萄糖的 de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe(MRS)培养基中,植物乳杆菌(Lactobacillus plantarum)EPS 的产量更高 [218]。培养基中碳源的不同也显著影响 EPS 的功能活性。例如,补充蔗糖的 MRS 培养基可显著增加植物乳杆菌(L. plantarum)LPC‑1 的 EPS 产量 [219];而使用葡萄糖时,该菌株报告了更高的抗氧化活性,相比于蔗糖条件 [219]。总体而言,乳酸杆菌菌株与碳源这两大因素的协同作用,会导致 EPS 在流变学特性上的差异,进而影响其功能活性。

乳酸杆菌 EPS 的独特理化特性有望为人类带来健康益处,已有研究报道其具备抗动脉粥样硬化、抗癌、抗氧化、抗病毒、抗真菌、免疫调节和益生元特性 [220–224]。人源防御素‑2(Human β‑Defensin 2)是宿主上皮细胞分泌的抗菌肽,有助于调节阴道黏膜的炎症及微生物群平衡 [225]。相应地,卷曲乳杆菌(Lactobacillus crispatus)L1 来源的 EPS 可显著增强阴道上皮细胞 VK2 对人源防御素‑2 的分泌,进而通过竞争性排斥机制减少白色念珠菌(Candida albicans)黏附 48% [226]。同样,鼠李糖乳杆菌(L. rhamnosus)GG 来源的 EPS 也在 VK2 细胞和人支气管上皮 Calu‑3 细胞系上分别将 C. albicans 黏附减少 30% 和将 C. glabrata 黏附减少 25% [224]。考量到酵母形态向菌丝形态的转化对 C. albicans 致病性及其免疫病理过程至关重要 [227],Allonsius 等人报告,L. rhamnosus GG EPS 能将 C. albicans 的菌丝形成抑制 40%,进一步证明了其潜在的抗念珠菌特性 [224]。细菌性阴道病(BV)以阴道上皮表面多种微生物生物膜的存在为特征 [228]。研究表明,植物乳杆菌(L. plantarum)WLPL04 来源的 EPS 可显著减少大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)、铜绿假单胞菌(Pseudomonas aeruginosa)、金黄色葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus aureus)和沙门氏菌(Salmonella typhimurium)在 HT‑29 细胞系上的黏附 [33],使其成为开发抗生物膜制剂、改善 BV 管理的潜在候选。

BV 的发生与阴道环境中高氧化应激(如丙二醛,MDA 水平升高及超氧化物歧化酶,SOD 活性降低)以及黏蛋白降解密切相关 [229, 230]。因此,阴道上皮具备较高的抗氧化能力或可减轻 BV 感染期间的氧化应激,并增强局部免疫防御。植物乳杆菌(L. plantarum)C88 来源的 EPS 已被证明以剂量依赖方式降低 MDA 水平并提高 SOD 活性,从而展现出强抗氧化效果 [231]。此外,从瑞士乳杆菌(L. helveticus)KLDS1.8701 提取的纯化 EPS 可显著提升小鼠肝脏的抗氧化酶活性,通过降低 SOD 水平来缓解氧化损伤 [232]。除抗氧化能力外,乳酸杆菌 EPS 还可促进黏蛋白屏障修复,例如,植物乳杆菌 EPS 可通过上调小鼠结肠中 MUC2 基因表达、紧密连接蛋白表达及杯状细胞分化,促进黏膜愈合与保护 [233, 234]。事实上,黏蛋白本身已被证实可防止病原菌黏附,并辅助乳酸菌在上皮细胞上的定殖 [25]。

EPS 的益生元特性也受到广泛关注。通常,一种化合物要被定义为“益生元”,需满足能耐受胃肠道酶降解和小肠吸收,并能在结肠发酵刺激有益菌生长的要求 [212]。Sims 等人表明,利用 β‑葡聚糖、菊粉和果寡糖等益生元寡糖,可显著促进乳酸菌(包括鼠李糖乳杆菌 GG)的生长,提示益生元与益生菌联合应用可为宿主提供更大健康益处 [235]。例如,短乳杆菌(L. brevis)ED25 来源的葡聚糖 EPS 可提高食品中 L. rhamnosus GG 的保质期和存活率 [236]。此外,益生菌 EPS 所释放的多糖被认为通过细菌间的分子对话增强肠道内正常菌群的丰度 [237]。由此可推测,类似的相互作用也可能在阴道环境中促进有益菌定殖与生长。

生物表面活性剂(BS)

生物表面活性剂(BS),也称为生物乳化剂,是主要由微生物合成的两亲性活性化合物 [238]。这些两亲性分子赋予微生物通过乳化降低水溶液间表面和界面张力的能力 [239]。生物BS可分为低分子量表面活性剂(如糖脂和脂肽)和高分子量表面活性剂(如糖蛋白复合物、脂多糖和脂蛋白) [240]。除了在农业、动物饲料、化妆品、食品和石油工业中的重要作用外,BS最近因其生物修复潜力而受到关注 [241, 242]。然而,乳酸菌BS的功能活性仍未被充分研究 [240]。Mouafo等人表明,乳酸菌BS的产生取决于发酵碳源的选择。甘蔗和甘油为碳源相比MRS培养基能显著提高BS产量 [243]。

生物表面活性剂被报道可通过改变微生物附着表面的化学性质而表现出抗黏附和抗菌特性 [182]。鼠李糖脂是一种通常由非致病性酵母 Starmerella bombicola 产生的糖脂BS [244]。该化合物已被证明能抑制白色念珠菌(C. albicans)生物膜的形成,并破坏预形成的生物膜 [244]。令人惊讶的是,Haque等人还发现,鼠李糖脂与抗真菌药物联合使用时,对抑制白色念珠菌具有协同增效作用,治疗后未观察到菌丝和复杂生物膜网络 [244]。

对于乳酸菌产生的BS,近期报道指出嗜酸乳杆菌(L. acidophilus)ATCC 4356、德氏乳杆菌(L. delbrueckii)ATCC 9645和副干酪乳杆菌(L. paracasei)11 的BS可显著减少阴道病原菌白色念珠菌(C. albicans)生物膜形成,抑制率达40–50% [245]。此外,短乳杆菌(L. brevis)CV8LAC 的BS在聚二甲基硅氧烷(PDMS)弹性板上对24、48 和72 小时的白色念珠菌生物膜形成具有约90%的抑制效果 [246]。

除了对白色念珠菌生物膜的抑制外,詹氏乳杆菌(L. jensenii)P6A 和加氏乳杆菌(L. gasseri)P65 的BS还对多种泌尿生殖道病原菌(如大肠杆菌 E. coli、肺炎克雷伯菌 K. pneumoniae、腐生葡萄球菌 S. saprophyticus 和产气肠杆菌 Enterobacter aerogenes)展现出强抗菌和抗生物膜活性 [247]。此外,粗制副干酪乳杆菌(L. paracasei)BS可抑制化脓性链球菌(S. pyogenes)、表皮葡萄球菌(S. epidermidis)、大肠杆菌(E. coli)、绿脓杆菌(P. aeruginosa)、金黄色葡萄球菌(S. aureus)和无乳链球菌(S. agalactiae) [248]。Gudiña等人发现,该BS在碱性条件(pH 6–10)和60 °C 热处理后仍高度稳定;通过酸性提取法获得的粗制BS抗菌活性进一步增强 [248]。

多项研究还探讨了乳酸菌BS对其他阴道和尿路病原菌的作用。Spurbeck 和 Arvidson 报道,加氏乳杆菌(L. gasseri)33323 BS通过阻断上皮细胞外基质成分纤维连接蛋白,表现出对淋病奈瑟氏菌(N. gonorrhoeae)的抗黏附活性 [249]。来自卷曲乳杆菌(L. crispatus)的BS在7 分钟和60 分钟孵育后,均能抑制淋病奈瑟氏菌生长超过50% [250]。Jiang等人指出,瑞士乳杆菌(L. helveticus)27170 BS 的抗黏附机制与干扰金黄色葡萄球菌自诱导物-2(AI-2 群体感应分子)信号有关 [251]。

此外,Satpute等人揭示,嗜酸乳杆菌(L. acidophilus)BS能够通过抗黏附作用,减少医疗植入物聚二甲基硅氧烷表面上大肠杆菌(E. coli)、金黄色葡萄球菌(S. aureus)、变形杆菌(P. vulgaris)、枯草杆菌(B. subtilis)和假单胞菌(P. putida)的生物膜形成 [252]。最近,卷曲乳杆菌(L. crispatus)BC1 BS 在人宫颈癌 HeLa 细胞系中通过排斥机制显示出显著的体外抗黏附活性,对抗白色念珠菌;在小鼠模型中则通过减少念珠菌引起的白细胞浸润(防止黏膜损伤)表现出体内免疫调节活性 [253]。

根据上述发现,可推测乳酸菌BS主要通过阻断黏附而非直接杀灭入侵病原菌来发挥作用。

乳酸杆菌SAMs应用的挑战

尽管有大量证据表明乳酸杆菌SAMs可能有益于人类,但其实施应用仍不明朗且具有挑战性。其中一个挑战是其生产所需的成本。由于其提取通常受到低产量的阻碍,优化生长培养基组成和提取方法至关重要 [210, 215, 254]。此外,碳源类型和pH值等其他因素也显著影响EPS结构和产量 [255]。因此,SAMs的大规模生产通常需要额外的投入,可能耗时且性价比低。此外,由于SAMs结构会随着培养基组成波动,其在大规模工业化中的应用前景尚不确定。

为了降低乳酸杆菌SAMs发酵的高成本,可使用富含碳的农业废弃物,如麸皮、甘蔗渣和甜菜糖蜜,作为替代培养基 [256]。利用低成本农废基培养基可以减少大规模发酵过程中的高额投入,并满足未来SAMs的市场需求。此外,通过确定在成本最低条件下的最高产培养基配方,也可进一步降低生产费用 [215]。例如,基于配方优化和生产可能性曲线(PPC)的经济模型评估嗜酸乳杆菌(L. acidophilus)EPS的碳源,以确定最佳培养基成分及最优生产方案(OPS)[215]。Lin等人指出,使用MRS-营养肉汤培养基生产嗜酸乳杆菌EPS,其单位产本较仅用MRS培养基降低了30%(7.5美元/公斤 vs. 11.0美元/公斤)[215]。

此外,统计设计也是优化培养基、实现最大SAMs产量的重要手段。常用于SAMs(如生物表面活性剂)生产的统计方法包括因子设计和响应面法(RSM)[257]。例如,Plackett–Burman设计(PBD)已应用于通过统计建模优化单因素和多因素(如碳源、氮源类型)配方,以降低鼠李糖乳杆菌(L. rhamnosus)EPS生产成本 [254];响应面法中的中心复合设计(CCD)则用于分析和评估植物乳杆菌(L. plantarum)EPS生产的生长动力学参数 [218]。简言之,经济建模与统计设计可以筛选关键配方要素,显著降低SAMs生产总体成本。

此外,通过基因工程改造SAMs生产菌株,可提升SAMs产量并提高回收率。例如,Li等人报告,通过重定向EPS合成所需的NADH途径,干酪乳杆菌(L. casei)LC2W的EPS产量增加了46% [258]。然而,工程菌株的安全性备受公众关注,通过给药前的严格安全评估可消除潜在风险 [259]。

虽然体外研究大量证明了SAMs在阴道感染预防中的潜力,但其体内疗效尚未充分验证。同时,异体免疫反应使得重建以乳酸杆菌为主的健康阴道菌群面临困难。因而,需要个性化的菌群干预策略来验证SAMs的临床效果 [260]。此外,阴道感染的高复发率表明传统抗菌手段在长期管理中存在瓶颈。借助乳酸杆菌及其SAMs衍生物,可实现阴道菌群的平衡恢复。未来研究应聚焦于开发经济可行的SAMs大规模制备技术,突破生产瓶颈,为阴道感染提供创新治疗方案。

结论

人类阴道中的微生物群与真菌群共存,塑造了阴道生态的健康与疾病状态。在过去十年中,阴道微生物群分析已被广泛开展。许多研究报告指出,健康阴道的微生物分类群(CST)通常以乳酸菌为主,厌氧菌多样性低,并具有平衡的阴道免疫反应(如促炎与抗炎细胞因子)。宿主易感性和遗传因素已被证明会改变阴道微生物组组成,因而失衡的阴道生态往往导致病态CST及症状性阴道炎。同时,乳酸杆菌在肠道和阴道中已展示出免疫调节及恢复健康微生物群的潜在益处。尽管在免疫缺陷患者中偶有乳酸杆菌菌血症报告,其在降低阴道感染复发率以及预防阴道获得性感染方面的正面效果已被充分证实。因此,应投入开发更多基于益生菌的治疗策略,以挖掘益生菌在免疫缺陷人群中的潜在优势。

将乳酸杆菌用作预防手段是一种长期有效的方法。如本综述所述,乳酸杆菌衍生物(即SAMs)可通过恢复原生微生物群及其抗生物膜能力,发挥阴道感染预防作用。在BV患者中,成功恢复以乳酸杆菌为主的菌群组合已被报道,复发率降低,同时BV相关病原(如加德纳菌、普氏菌、大球菌、棒杆菌科和阿托波菌)显著减少 [261]。乳酸杆菌SAMs对抗阴道病原菌的作用包括抗生物膜、抗氧化、抗病毒、病原抑制和免疫调节,直接参与宿主与阴道微生物群的相互作用。鉴于乳酸杆菌SAMs在体外显著抑制阴道病原菌生长,后续研究应聚焦其在体内模型中的作用机制。这将是理解乳酸杆菌及其衍生物调节阴道黏膜屏障、抵御侵袭性病原体的重要工具。对乳酸杆菌SAMs及其作用机制的新知,将极大促进益生元与抗菌制剂的开发,旨在预防与治疗BV、性传播感染和阴道念珠菌病等阴道疾病。

本文翻译自论文

Jeng, W. Y. C., Chew, S. Y., & Than, L. T. L. (2020). Vaginal microbiota and the potential of Lactobacillus derivatives in maintaining vaginal health. Microbial Cell Factories, 19, 203. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-01464-4

参考文献:

1.Lloyd-Price J, Mahurkar A, Rahnavard G, Crabtree J, Orvis J, Hall AB, et al. Strains, functions and dynamics in the expanded Human Microbiome Project. Nature. 2017;550:61–6. doi: 10.1038/nature23889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2.Proctor LM, Creasy HH, Fettweis JM, Lloyd-Price J, Mahurkar A, Zhou W, et al. The integrative Human Microbiome Project. Nature. 2019;569:641–8. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-01654-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI. The Human Microbiome Project. Nature. 2007;449:804–10. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4.Cho I, Blaser MJ. The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:260–70. doi: 10.1038/nrg3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5.Smith SB, Ravel J. The vaginal microbiota, host defence and reproductive physiology. J Physiol. 2017;595:451–63. doi: 10.1113/JP271694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6.Gajer P, Brotman RM, Bai G, Sakamoto J, Schütte UME, Zhong X, et al. Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:132ra52. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7.Fredricks DN. Molecular methods to describe the spectrum and dynamics of the vaginal microbiota. Anaerobe. 2011;17:191–5. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8.Franzosa EA, Hsu T, Sirota-Madi A, Shafquat A, Abu-Ali G, Morgan XC, et al. Sequencing and beyond: integrating molecular ‘omics’ for microbial community profiling. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:360–72. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9.Johnson JS, Spakowicz DJ, Hong B-Y, Petersen LM, Demkowicz P, Chen L, et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5029. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13036-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10.Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SSK, McCulle SL, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4680–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11.Ma B, Forney LJ, Ravel J. Vaginal microbiome: rethinking health and disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:371–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12.Hall RA, Noverr MC. Fungal interactions with the human host: exploring the spectrum of symbiosis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2017;40:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13.Gow NAR, Hube B. Importance of the Candida albicans cell wall during commensalism and infection. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2012;15:406–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14.Zapata HJ, Quagliarello VJ. The microbiota and microbiome in aging: potential implications in health and age-related diseases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:776–81. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15.Plummer EL, Vodstrcil LA, Fairley CK, Tabrizi SN, Garland SM, Law MG, et al. Sexual practices have a significant impact on the vaginal microbiota of women who have sex with women. Sci Rep. 2019;9:19749. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55929-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16.Mulder M, Radjabzadeh D, Hassing RJ, Heeringa J, Uitterlinden AG, Kraaij R, et al. The effect of antimicrobial drug use on the composition of the genitourinary microbiota in an elderly population. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:9. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1379-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17.Hickey RJ, Zhou X, Settles ML, Erb J, Malone K, Hansmann MA, et al. Vaginal microbiota of adolescent girls prior to the onset of menarche resemble those of reproductive-age women. mBio. 2015;6:e00097-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00097-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18.Bradford LL, Chibucos MC, Ma B, Bruno V, Ravel J. Vaginal Candida spp. genomes from women with vulvovaginal candidiasis. Pathog Dis. 2017;75:ftx061. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftx061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19.Mitra A, MacIntyre DA, Marchesi JR, Lee YS, Bennett PR, Kyrgiou M. The vaginal microbiota, human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: what do we know and where are we going next? Microbiome. 2016;4:58. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20.van de Wijgert JHHM. The vaginal microbiome and sexually transmitted infections are interlinked: consequences for treatment and prevention. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21.Ziklo N, Vidgen ME, Taing K, Huston WM, Timms P. Dysbiosis of the vaginal microbiota and higher vaginal kynurenine/tryptophan ratio reveals an association with Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:1. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22.Shannon B, Gajer P, Yi TJ, Ma B, Humphrys MS, Thomas-Pavanel J, et al. Distinct effects of the cervicovaginal microbiota and herpes simplex type 2 infection on female genital tract immunology. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1366–75. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23.Eastment MC, McClelland RS. Vaginal microbiota and susceptibility to HIV. AIDS. 2018;32:687–98. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24.Ceccarani C, Foschi C, Parolin C, D’Antuono A, Gaspari V, Consolandi C, et al. Diversity of vaginal microbiome and metabolome during genital infections. Sci Rep. 2019;9::14095. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50410-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25.Amabebe E, Anumba DOC. The vaginal microenvironment: the physiologic role of lactobacilli. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018;5:181. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26.O’Toole PW, Marchesi JR, Hill C. Next-generation probiotics: the spectrum from probiotics to live biotherapeutics. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17057. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27.van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, Fuentes S, Zoetendal EG, de Vos WM, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28.Lev-Sagie A, Goldman-Wohl D, Cohen Y, Dori-Bachash M, Leshem A, Mor U, et al. Vaginal microbiome transplantation in women with intractable bacterial vaginosis. Nat Med. 2019;25:1500–4. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29.Larsson P-G, Brandsborg E, Forsum U, Pendharkar S, Andersen KK, Nasic S, et al. Extended antimicrobial treatment of bacterial vaginosis combined with human lactobacilli to find the best treatment and minimize the risk of relapses. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:223. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30.Anukam K, Osazuwa E, Ahonkhai I, Ngwu M, Osemene G, Bruce AW, et al. Augmentation of antimicrobial metronidazole therapy of bacterial vaginosis with oral probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1450–4. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31.Castro-Bravo N, Wells JM, Margolles A, Ruas-Madiedo P. Interactions of surface exopolysaccharides from Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus within the intestinal environment. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2426. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32.Kleerebezem M, Hols P, Bernard E, Rolain T, Zhou M, Siezen RJ, et al. The extracellular biology of the lactobacilli. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34:199–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33.Liu Z, Zhang Z, Qiu L, Zhang F, Xu X, Wei H, et al. Characterization and bioactivities of the exopolysaccharide from a probiotic strain of Lactobacillus plantarum WLPL04. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:6895–905. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34.Allonsius CN, Vandenheuvel D, Oerlemans EFM, Petrova MI, Donders GGG, Cos P, et al. Inhibition of Candida albicans morphogenesis by chitinase from Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Sci Rep. 2019;9:2900. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39625-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35.Ahn KB, Baik JE, Park O-J, Yun C-H, Han SH. Lactobacillus plantarum lipoteichoic acid inhibits biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36.Brooks JP, Buck GA, Chen G, Diao L, Edwards DJ, Fettweis JM, et al. Changes in vaginal community state types reflect major shifts in the microbiome. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2017;28:1303265. doi: 10.1080/16512235.2017.1303265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37.Zheng N, Guo R, Yao Y, Jin M, Cheng Y, Ling Z. Lactobacillus iners is associated with vaginal dysbiosis in healthy pregnant women: a preliminary study. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:6079734. doi: 10.1155/2019/6079734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38.Li F, Brix S, Wang Z, Chen C, Song L, Hao L, et al. The metagenome of the female upper reproductive tract. Gigascience. 2018;7:giy107. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39.Drell T, Lillsaar T, Tummeleht L, Simm J, Aaspõllu A, Väin E, et al. Characterization of the vaginal micro- and mycobiome in asymptomatic reproductive-age Estonian women. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40.Kroon SJ, Ravel J, Huston WM. Cervicovaginal microbiota, women’s health, and reproductive outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41.Younes JA, Lievens E, Hummelen R, van der Westen R, Reid G, Petrova MI. Women and their microbes: the unexpected friendship. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:16–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42.Hickey RJ, Zhou X, Pierson JD, Ravel J, Forney LJ. Understanding vaginal microbiome complexity from an ecological perspective. Transl Res. 2012;160:267–82. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43.Sabo MC, Balkus JE, Richardson BA, Srinivasan S, Kimani J, Anzala O, et al. Association between vaginal washing and vaginal bacterial concentrations. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0210825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44.Huang B, Fettweis JM, Brooks JP, Jefferson KK, Buck GA. The changing landscape of the vaginal microbiome. Clin Lab Med. 2014;34:747–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45.Doyle R, Gondwe A, Fan Y-M, Maleta K, Ashorn P, Klein N, et al. A Lactobacillus-deficient vaginal microbiota dominates postpartum women in rural Malawi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84:e02150-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02150-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46.van de Wijgert JHHM, Borgdorff H, Verhelst R, Crucitti T, Francis S, Verstraelen H, et al. The vaginal microbiota: what have we learned after a decade of molecular characterization? PLoS One. 2014;9:e105998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47.DiGiulio DB, Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Costello EK, Lyell DJ, Robaczewska A, et al. Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:11060–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502875112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48.De Seta F, Campisciano G, Zanotta N, Ricci G, Comar M. The vaginal community state types microbiome-immune network as key factor for bacterial vaginosis and aerobic vaginitis. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2451. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49.Jakobsson T, Forsum U. Lactobacillus iners: a marker of changes in the vaginal flora? J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3145. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00558-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50.Verstraelen H, Verhelst R, Claeys G, De Backer E, Temmerman M, Vaneechoutte M. Longitudinal analysis of the vaginal microflora in pregnancy suggests that L. crispatus promotes the stability of the normal vaginal microflora and that L. gasseri and/or L. iners are more conducive to the occurrence of abnormal vaginal microflora. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51.Breshears LM, Edwards VL, Ravel J, Peterson ML. Lactobacillus crispatus inhibits growth of Gardnerella vaginalis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae on a porcine vaginal mucosa model. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:276. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0608-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52.Fuochi V, Cardile V, Petronio Petronio G, Furneri PM. Biological properties and production of bacteriocins-like-inhibitory substances by Lactobacillus sp. strains from human vagina. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;126:1541–50. doi: 10.1111/jam.14164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53.France MT, Mendes-Soares H, Forney LJ. Genomic comparisons of Lactobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus iners reveal potential ecological drivers of community composition in the vagina. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:7063–73. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02385-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54.Edwards VL, Smith SB, McComb EJ, Tamarelle J, Ma B, Humphrys MS, et al. The cervicovaginal microbiota-host interaction modulates Chlamydia trachomatis infection. mBio. 2019;10:e01548-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01548-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55.Witkin SS, Mendes-Soares H, Linhares IM, Jayaram A, Ledger WJ, Forney LJ. Influence of vaginal bacteria and D- and L-lactic acid isomers on vaginal extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer: implications for protection against upper genital tract infections. mBio. 2013;4:e00460-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00460-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56.Borgdorff H, van der Veer C, van Houdt R, Alberts CJ, de Vries HJ, Bruisten SM, et al. The association between ethnicity and vaginal microbiota composition in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57.van de Wijgert JHHM, Verwijs MC, Gill AC, Borgdorff H, van der Veer C, Mayaud P. Pathobionts in the vaginal microbiota: individual participant data meta-analysis of three sequencing studies. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:129. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58.Kwak W, Han Y-H, Seol D, Kim H, Ahn H, Jeong M, et al. Complete genome of Lactobacillus iners KY using Flongle provides insight into the genetic background of optimal adaption to vaginal econiche. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1048. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59.Chao X-P, Sun T-T, Wang S, Fan Q-B, Shi H-H, Zhu L, et al. Correlation between the diversity of vaginal microbiota and the risk of high-risk human papillomavirus infection. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29:28–34. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2018-000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60.Kyrgiou M, Mitra A, Moscicki A-B. Does the vaginal microbiota play a role in the development of cervical cancer? Transl Res. 2017;179:168–82. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61.Lee JE, Lee S, Lee H, Song Y-M, Lee K, Han MJ, et al. Association of the vaginal microbiota with human papillomavirus infection in a Korean twin cohort. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62.Kwasniewski W, Wolun-Cholewa M, Kotarski J, Warchol W, Kuzma D, Kwasniewska A, et al. Microbiota dysbiosis is associated with HPV-induced cervical carcinogenesis. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:7035–47. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63.Zhou Y, Wang L, Pei F, Ji M, Zhang F, Sun Y, et al. Patients with LR-HPV infection have a distinct vaginal microbiota in comparison with healthy controls. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:294. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64.Brusselaers N, Shrestha S, van de Wijgert J, Verstraelen H. Vaginal dysbiosis and the risk of human papillomavirus and cervical cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:9–18.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65.Mathema B, Cross E, Dun E, Park S, Bedell J, Slade B, et al. Prevalence of vaginal colonization by drug-resistant Candida species in college-age women with previous exposure to over-the-counter azole antifungals. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:e23-7. doi: 10.1086/322600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66.Farr A, Kiss H, Holzer I, Husslein P, Hagmann M, Petricevic L. Effect of asymptomatic vaginal colonization with Candida albicans on pregnancy outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94:989–96. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67.Ward TL, Dominguez-Bello MG, Heisel T, Al-Ghalith G, Knights D, Gale CA. Development of the human mycobiome over the first month of life and across body sites. mSystems. 2018;3:e00140-17. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00140-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68.Bliss JM, Basavegowda KP, Watson WJ, Sheikh AU, Ryan RM. Vertical and horizontal transmission of Candida albicans in very low birth weight infants using DNA fingerprinting techniques. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:231–5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31815bb69d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69.Brown SE, Schwartz JA, Robinson CK, O’Hanlon DE, Bradford LL, He X, et al. The vaginal microbiota and behavioral factors associated with genital Candida albicans detection in reproductive-age women. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46:753–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70.Guzel AB, Ilkit M, Akar T, Burgut R, Demir SC. Evaluation of risk factors in patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis and the value of chromID Candida agar versus CHROMagar Candida for recovery and presumptive identification of vaginal yeast species. Med Mycol. 2011;49:16–25. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.497972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71.Gonçalves B, Ferreira C, Alves CT, Henriques M, Azeredo J, Silva S. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiology, microbiology and risk factors. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2016;42:905–27. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2015.1091805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72.Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal candidosis. Lancet. 2007;369::1961–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73.Fidel PL, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD. Candida glabrata: review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:80–96. doi: 10.1128/CMR.12.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74.Denning DW, Kneale M, Sobel JD, Rautemaa-Richardson R. Global burden of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:e339-47. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75.Förster TM, Mogavero S, Dräger A, Graf K, Polke M, Jacobsen ID, et al. Enemies and brothers in arms: Candida albicans and gram-positive bacteria. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18:1709–15. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76.Sadeghi G, Ebrahimi-Rad M, Mousavi SF, Shams-Ghahfarokhi M, Razzaghi-Abyaneh M. Emergence of non-Candida albicans species: epidemiology, phylogeny and fluconazole susceptibility profile. J Mycol Med. 2018;28:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77.Ng KP, Kuan CS, Kaur H, Na SL, Atiya N, Velayuthan RD. Candida species epidemiology 2000–2013: a laboratory-based report. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20:1447–53. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78.Bitew A, Abebaw Y. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: species distribution of Candida and their antifungal susceptibility pattern. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:94. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0607-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79.De Vos MM, Cuenca-Estrella M, Boekhout T, Theelen B, Matthijs N, Bauters T, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis in a Flemish patient population. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:1005–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80.Rodríguez-Cerdeira C, Gregorio MC, Molares-Vila A, López-Barcenas A, Fabbrocini G, Bardhi B, et al. Biofilms and vulvovaginal candidiasis. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019;174:110–25. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81.Aballéa S, Guelfucci F, Wagner J, Khemiri A, Dietz J-P, Sobel J, et al. Subjective health status and health-related quality of life among women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis (RVVC) in Europe and the USA. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:169. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82.Nobile CJ, Johnson AD. Candida albicans biofilms and human disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2015;69:71–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83.Berman J. Candida albicans. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R620-2. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84.Bradford LL, Ravel J. The vaginal mycobiome: a contemporary perspective on fungi in women’s health and diseases. Virulence. 2017;8:342–51. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1237332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85.Swidsinski A, Guschin A, Tang Q, Dörffel Y, Verstraelen H, Tertychnyy A, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: histologic lesions are primarily polymicrobial and invasive and do not contain biofilms. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220::91.e91-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86.Roselletti E, Monari C, Sabbatini S, Perito S, Vecchiarelli A, Sobel JD, et al. A role for yeast/pseudohyphal cells of Candida albicans in the correlated expression of NLRP3 inflammasome inducers in women with acute vulvovaginal candidiasis. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2669. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87.Krüger W, Vielreicher S, Kapitan M, Jacobsen ID, Niemiec MJ. Fungal-bacterial interactions in health and disease. Pathogens. 2019;8:70. doi: 10.3390/pathogens8020070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88.Guo R, Zheng N, Lu H, Yin H, Yao J, Chen Y. Increased diversity of fungal flora in the vagina of patients with recurrent vaginal candidiasis and allergic rhinitis. Microb Ecol. 2012;64:918–27. doi: 10.1007/s00248-012-0084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89.Zheng N-N, Guo X-C, Lv W, Chen X-X, Feng G-F. Characterization of the vaginal fungal flora in pregnant diabetic women by 18S rRNA sequencing. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:1031–40. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1847-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90.Bradshaw CS, Brotman RM. Making inroads into improving treatment of bacterial vaginosis – striving for long-term cure. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:292. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91.Peebles K, Velloza J, Balkus JE, McClelland RS, Barnabas RV. High global burden and costs of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review and meta-Analysis. Sex Transm Dis. 2019;46:304–11. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92.Coleman JS, Gaydos CA. Molecular diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis: an update. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e00342-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00342-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93.Muzny CA, Laniewski P, Schwebke JR, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Host–vaginal microbiota interactions in the pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2020;33:59–65. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94.Ravel J, Brotman RM, Gajer P, Ma B, Nandy M, Fadrosh DW, et al. Daily temporal dynamics of vaginal microbiota before, during and after episodes of bacterial vaginosis. Microbiome. 2013;1::29. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95.Shimaoka M, Yo Y, Doh K, Kotani Y, Suzuki A, Tsuji I, et al. Association between preterm delivery and bacterial vaginosis with or without treatment. Sci Rep. 2019;9:509. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36964-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96.Gondwe T, Ness R, Totten PA, Astete S, Tang G, Gold MA, et al. Novel bacterial vaginosis-associated organisms mediate the relationship between vaginal douching and pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect. 2020;96:439–44. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2019-054191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97.Bayigga L, Kateete DP, Anderson DJ, Sekikubo M, Nakanjako D. Diversity of vaginal microbiota in sub-Saharan Africa and its effects on HIV transmission and prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:155–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98.Bilardi JE, Walker S, Temple-Smith M, McNair R, Mooney-Somers J, Bellhouse C, et al. The burden of bacterial vaginosis: women’s experience of the physical, emotional, sexual and social impact of living with recurrent bacterial vaginosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99.Soper DE. Bacterial vaginosis and surgical site infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;222:219–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100.Muzny CA, Taylor CM, Swords WE, Tamhane A, Chattopadhyay D, Cerca N, et al. An updated conceptual model on the pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2019;220:1399–405. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101.Muzny CA, Blanchard E, Taylor CM, Aaron KJ, Talluri R, Griswold ME, et al. Identification of key bacteria involved in the induction of incident bacterial vaginosis: a prospective study. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:966–78. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102.Gilbert NM, Lewis WG, Li G, Sojka DK, Lubin JB, Lewis AL. Gardnerella vaginalis and Prevotella bivia trigger distinct and overlapping phenotypes in a mouse model of bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2019;220:1099–108. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103.Castro J, Machado D, Cerca N. Unveiling the role of Gardnerella vaginalis in polymicrobial bacterial vaginosis biofilms: the impact of other vaginal pathogens living as neighbors. ISME J. 2019;13:1306–17. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0337-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104.Swidsinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, Swidsinski S, Dörffel Y, Scholze J, et al. An adherent Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm persists on the vaginal epithelium after standard therapy with oral metronidazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198::97.e91-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105.Machado A, Cerca N. Influence of biofilm formation by Gardnerella vaginalis and other anaerobes on bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1856–61. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106.Gosmann C, Anahtar MN, Handley SA, Farcasanu M, Abu-Ali G, Bowman BA, et al. Lactobacillus-deficient cervicovaginal bacterial communities are associated with increased HIV acquisition in young South African women. Immunity. 2017;46:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107.Peipert JF, Lapane KL, Allsworth JE, Redding CA, Blume JD, Stein MD. Bacterial vaginosis, race, and sexually transmitted infections: does race modify the association? Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:363–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815e4179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108.McClelland RS, Lingappa JR, Srinivasan S, Kinuthia J, John-Stewart GC, Jaoko W, et al. Evaluation of the association between the concentrations of key vaginal bacteria and the increased risk of HIV acquisition in African women from five cohorts: a nested case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:554–64. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30058-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109.Cone RA. Vaginal microbiota and sexually transmitted infections that may influence transmission of cell-associated HIV. J Infect Dis. 2014;210::616-21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110.Nardini P, Ñahui Palomino RA, Parolin C, Laghi L, Foschi C, Cevenini R, et al. Lactobacillus crispatus inhibits the infectivity of Chlamydia trachomatis elementary bodies, in vitro study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29024. doi: 10.1038/srep29024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111.Gong Z, Luna Y, Yu P, Fan H. Lactobacilli inactivate Chlamydia trachomatis through lactic acid but not H2O2. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e107758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112.Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Korenromp E, Low N, Unemo M, Abu-Raddad LJ, et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97:548-62P. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.228486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113.Harp DF, Chowdhury I. Trichomoniasis: evaluation to execution. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;157:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

114.McCormack D, Koons K. Sexually transmitted infections. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2019;37:725–38. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2019.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115.Eisinger RW, Erbelding E, Fauci AS. Refocusing research on sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:1432–1434. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116.Zhu H, Shen Z, Luo H, Zhang W, Zhu X. Chlamydia trachomatis infection-associated risk of cervical cancer: a meta-analysis. Med (Baltim) 2016;95:e3077. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117.Johnson HL, Ghanem KG, Zenilman JM, Erbelding EJ. Sexually transmitted infections and adverse pregnancy outcomes among women attending inner city public sexually transmitted diseases clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:167–71. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f2e85f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118.van de Wijgert JHHM, Morrison CS, Brown J, Kwok C, Van Der Pol B, Chipato T, et al. Disentangling contributions of reproductive tract infections to HIV acquisition in African women. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:357–64. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a4f695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119.Masson L, Barnabas S, Deese J, Lennard K, Dabee S, Gamieldien H, et al. Inflammatory cytokine biomarkers of asymptomatic sexually transmitted infections and vaginal dysbiosis: a multicentre validation study. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95:5–12. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

120.Brotman RM, Bradford LL, Conrad M, Gajer P, Ault K, Peralta L, et al. Association between Trichomonas vaginalis and vaginal bacterial community composition among reproductive-age women. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:807–12. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182631c79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

121.Galvin SR, Cohen MS. The role of sexually transmitted diseases in HIV transmission. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:33–42. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122.Lewis J, Price MJ, Horner PJ, White PJ. Genital Chlamydia trachomatis infections clear more slowly in men than women, but are less likely to become established. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:237–44. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123.Stapleton AE. The vaginal microbiota and urinary tract infection. Microbiol Spectrom. 2016 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0025-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124.Qiao L-D, Chen S, Yang Y, Zhang K, Zheng B, Guo H-F, et al. Characteristics of urinary tract infection pathogens and their in vitro susceptibility to antimicrobial agents in China: data from a multicenter study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e004152. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125.Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:269–84. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126.Kline KA, Lewis AL. Gram-positive uropathogens, polymicrobial urinary tract infection, and the emerging microbiota of the urinary tract. Microbiol Spectr. 2016 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0012-2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

127.Kwon YE, Oh D-J, Kim MJ, Choi HM. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of asymptomatic pyuria in chronic kidney disease. Ann Lab Med. 2020;40:238–44. doi: 10.3343/alm.2020.40.3.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

128.Chu CM, Lowder JL. Diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections across age groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

129.Thomas-White K, Forster SC, Kumar N, Van Kuiken M, Putonti C, Stares MD, et al. Culturing of female bladder bacteria reveals an interconnected urogenital microbiota. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1557. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03968-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

130.Terlizzi ME, Gribaudo G, Maffei ME. UroPathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) infections: virulence factors, bladder responses, antibiotic, and non-antibiotic antimicrobial strategies. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1566. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

131.Komesu YM, Dinwiddie DL, Richter HE, Lukacz ES, Sung VW, Siddiqui NY, et al. Defining the relationship between vaginal and urinary microbiomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:151.e1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

132.Kirjavainen PV, Pautler S, Baroja ML, Anukam K, Crowley K, Carter K, et al. Abnormal immunological profile and vaginal microbiota in women prone to urinary tract infections. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:29–36. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00323-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

133.Gilbert NM, O’Brien VP, Lewis AL. Transient microbiota exposures activate dormant Escherichia coli infection in the bladder and drive severe outcomes of recurrent disease. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006238. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

134.Pierson JD, Hansmann MA, Davis CC, Forney LJ. The effect of vaginal microbial communities on colonization by Staphylococcus aureus with the gene for toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1): a case–control study. Pathog Dis. 2018;76:fty015. doi: 10.1093/femspd/fty015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

135.Schlievert PM, Nemeth KA, Davis CC, Peterson ML, Jones BE. Staphylococcus aureus exotoxins are present in vivo in tampons. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:722–7. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00483-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

136.Schlievert PM. Effect of non-absorbent intravaginal menstrual/contraceptive products on Staphylococcus aureus and production of the superantigen TSST-1. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39:31–8. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03685-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

137.Nonfoux L, Chiaruzzi M, Badiou C, Baude J, Tristan A, Thioulouse J, et al. Impact of currently marketed tampons and menstrual cups on Staphylococcus aureus growth and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 production in vitro. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84:e00351-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00351-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

138.Carter K, Bassis C, McKee K, Bullock K, Eastman A, Young V, et al. The impact of tampon use on the vaginal microbiota across four menstrual cycles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:639. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

139.MacPhee RA, Miller WL, Gloor GB, McCormick JK, Hammond J-A, Burton JP, et al. Influence of the vaginal microbiota on toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 production by Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:1835–42. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02908-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

140.Leroy F, De Vuyst L. Lactic acid bacteria as functional starter cultures for the food fermentation industry. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2004;15:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2003.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

141.George F, Daniel C, Thomas M, Singer E, Guilbaud A, Tessier FJ, et al. Occurrence and dynamism of lactic acid bacteria in distinct ecological niches: a multifaceted functional health perspective. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2899. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

142.Kerry RG, Patra JK, Gouda S, Park Y, Shin H-S, Das G. Benefaction of probiotics for human health: a review. J Food Drug Anal. 2018;26:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

143.Ghosh T, Beniwal A, Semwal A, Navani NK. Mechanistic insights into probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria associated with ethnic fermented dairy products. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:502. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

144.Mattia A, Merker R. Regulation of probiotic substances as ingredients in foods: premarket approval or “Generally Recognized as Safe” notification. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46::115-8. doi: 10.1086/523329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

145.Venegas-Ortega MG, Flores-Gallegos AC, Martínez-Hernández JL, Aguilar CN, Nevárez-Moorillón GV. Production of bioactive peptides from lactic acid bacteria: a sustainable approach for healthier foods. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2019;18:1039–51. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

146.Iyer R, Tomar SK, Uma Maheswari T, Singh R. Streptococcus thermophilus strains: multifunctional lactic acid bacteria. Int Dairy J. 2010;20:133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2009.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

147.Cui Y, Xu T, Qu X, Hu T, Jiang X, Zhao C. New insights into various production characteristics of Streptococcus thermophilus strains. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1701. doi: 10.3390/ijms17101701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

148.Reid G, Younes JA, Van der Mei HC, Gloor GB, Knight R, Busscher HJ. Microbiota restoration: natural and supplemented recovery of human microbial communities. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;9:27. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

149.Prabhurajeshwar C, Chandrakanth RK. Probiotic potential of lactobacilli with antagonistic activity against pathogenic strains: an in vitro validation for the production of inhibitory substances. Biomed J. 2017;40:270–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

150.Chew SY, Cheah YK, Seow HF, Sandai D, Than LTL. Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14 exhibit strong antifungal effects against vulvovaginal candidiasis-causing Candida glabrata isolates. J Appl Microbiol. 2015;118:1180–90. doi: 10.1111/jam.12772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

151.Singh TP, Kaur G, Kapila S, Malik RK. Antagonistic activity of Lactobacillus reuteri strains on the adhesion characteristics of selected pathogens. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:486. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

152.Humphreys GJ, McBain AJ. Antagonistic effects of Streptococcus and Lactobacillus probiotics in pharyngeal biofilms. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2019;68:303–12. doi: 10.1111/lam.13133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

153.Gaspar C, Donders GG, Palmeira-de-Oliveira R, Queiroz JA, Tomaz C, Martinez-de-Oliveira J, et al. Bacteriocin production of the probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus KS400. AMB Express. 2018;8:153. doi: 10.1186/s13568-018-0679-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

154.Turovskiy Y, Ludescher RD, Aroutcheva AA, Faro S, Chikindas ML. Lactocin 160, a bacteriocin produced by vaginal Lactobacillus rhamnosus, targets cytoplasmic membranes of the vaginal pathogen, Gardnerella vaginalis. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2009;1:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s12602-008-9003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

155.Donders GGG, Ruban K, Bellen G. Selecting anti-microbial treatment of aerobic vaginitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2015;17:477. doi: 10.1007/s11908-015-0477-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

156.Donders GGG, Bellen G, Grinceviciene S, Ruban K, Vieira-Baptista P. Aerobic vaginitis: no longer a stranger. Res Microbiol. 2017;168:845–58. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

157.Beigi RH, Austin MN, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Antimicrobial resistance associated with the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1124–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

158.Austin MN, Beigi RH, Meyn LA, Hillier SL. Microbiologic response to treatment of bacterial vaginosis with topical clindamycin or metronidazole. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4492–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4492-4497.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

159.Bertuccini L, Russo R, Iosi F, Superti F. Effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus acidophilus on bacterial vaginal pathogens. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2017;30:163–7. doi: 10.1177/0394632017697987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

160.De Alberti D, Russo R, Terruzzi F, Nobile V, Ouwehand AC. Lactobacilli vaginal colonisation after oral consumption of Respecta® complex: a randomised controlled pilot study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:861–7. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3711-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

161.Mezzasalma V, Manfrini E, Ferri E, Boccarusso M, Di Gennaro P, Schiano I, et al. Orally administered multispecies probiotic formulations to prevent uro-genital infections: a randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:163–72. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

162.Wang S, Wang Q, Yang E, Yan L, Li T, Zhuang H. Antimicrobial compounds produced by vaginal Lactobacillus crispatus are able to strongly inhibit Candida albicans growth, hyphal formation and regulate virulence-related gene expressions. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:564. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

163.Li T, Liu Z, Zhang X, Chen X, Wang S. Local probiotic Lactobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii exhibit strong antifungal effects against vulvovaginal candidiasis in a rat model. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1033. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

164.Heczko PB, Tomusiak A, Adamski P, Jakimiuk AJ, Stefański G, Mikołajczyk-Cichońska A, et al. Supplementation of standard antibiotic therapy with oral probiotics for bacterial vaginosis and aerobic vaginitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:115. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0246-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

165.Balzaretti S, Taverniti V, Rondini G, Marcolegio G, Minuzzo M, Remagni MC, et al. The vaginal isolate Lactobacillus paracasei LPC-S01 (DSM 26760) is suitable for oral administration. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:952. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

166.Reid G, Bruce AW, Fraser N, Heinemann C, Owen J, Henning B. Oral probiotics can resolve urogenital infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2001;30:49–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2001.tb01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

167.Buggio L, Somigliana E, Borghi A, Vercellini P. Probiotics and vaginal microecology: fact or fancy? BMC Womens Health. 2019;19:25. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0723-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

168.Bohbot JM, Daraï E, Bretelle F, Brami G, Daniel C, Cardot JM. Efficacy and safety of vaginally administered lyophilized Lactobacillus crispatus IP 174178 in the prevention of bacterial vaginosis recurrence. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2018;47:81–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

169.Vicariotto F, Mogna L, Del Piano M. Effectiveness of the two microorganisms Lactobacillus fermentum LF15 and Lactobacillus plantarum LP01, formulated in slow-release vaginal tablets, in women affected by bacterial vaginosis: a pilot study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:106–112. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

170.Palma E, Recine N, Domenici L, Giorgini M, Pierangeli A, Panici PB. Long-term Lactobacillus rhamnosus BMX 54 application to restore a balanced vaginal ecosystem: a promising solution against HPV-infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:13. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2938-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

171.Recine N, Palma E, Domenici L, Giorgini M, Imperiale L, Sassu C, et al. Restoring vaginal microbiota: biological control of bacterial vaginosis. A prospective case–control study using Lactobacillus rhamnosus BMX 54 as adjuvant treatment against bacterial vaginosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:101–7. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3810-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

172.van de Wijgert JHHM, Verwijs MC, Agaba SK, Bronowski C, Mwambarangwe L, Uwineza M, et al. Intermittent lactobacilli-containing vaginal probiotic or metronidazole use to prevent bacterial vaginosis recurrence: a pilot study incorporating microscopy and sequencing. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3884. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60671-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

173.Russo R, Superti F, Karadja E, De Seta F. Randomised clinical trial in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: efficacy of probiotics and lactoferrin as maintenance treatment. Mycoses. 2019;62:328–35. doi: 10.1111/myc.12883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

174.Xie HY, Feng D, Wei DM, Mei L, Chen H, Wang X, et al. Probiotics for vulvovaginal candidiasis in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD010496. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010496.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

175.Chehoud C, Stieh DJ, Bailey AG, Laughlin AL, Allen SA, McCotter KL, et al. Associations of the vaginal microbiota with HIV infection, bacterial vaginosis, and demographic factors. AIDS. 2017;31:895–904. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

176.Spear GT, St John E, Zariffard M. Bacterial vaginosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection. AIDS Res Ther. 2007;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

177.Brichacek B, Lagenaur LA, Lee PP, Venzon D, Hamer DH. In vivo evaluation of safety and toxicity of a Lactobacillus jensenii producing modified cyanovirin-N in a rhesus macaque vaginal challenge model. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

178.Palomino RAN, Zicari S, Vanpouille C, Vitali B, Margolis L. Vaginal Lactobacillus inhibits HIV-1 replication in human tissues ex vivo. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:906. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

179.Martín V, Maldonado A, Fernández L, Rodríguez JM, Connor RI. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by lactic acid bacteria from human breastmilk. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5:153–8. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2010.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

180.Su Y, Zhang B, Su L. CD4 detected from Lactobacillus helps understand the interaction between Lactobacillus and HIV. Microbiol Res. 2013;168:273–7. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

181.Palomino RAÑ, Vanpouille C, Laghi L, Parolin C, Melikov K, Backlund P, et al. Extracellular vesicles from symbiotic vaginal lactobacilli inhibit HIV-1 infection of human tissues. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5656. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

182.Spurbeck RR, Arvidson CG. Lactobacilli at the front line of defense against vaginally acquired infections. Future Microbiol. 2011;6:567–82. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

183.Sanders ME, Merenstein DJ, Reid G, Gibson GR, Rastall RA. Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: from biology to the clinic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:605–16. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

184.Lebeer S, Vanderleyden J, De Keersmaecker SCJ. Genes and molecules of lactobacilli supporting probiotic action. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:728–64. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00017-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

185.Lebeer S, Vanderleyden J, De Keersmaecker SC. Host interactions of probiotic bacterial surface molecules: comparison with commensals and pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:171–84. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

186.Hajfarajollah H, Eslami P, Mokhtarani B, Akbari Noghabi K. Biosurfactants from probiotic bacteria: a review. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2018;65:768–83. doi: 10.1002/bab.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

187.Sanders ME, Benson A, Lebeer S, Merenstein DJ, Klaenhammer TR. Shared mechanisms among probiotic taxa: implications for general probiotic claims. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2018;49:207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

188.Duchêne M-C, Rolain T, Knoops A, Courtin P, Chapot-Chartier M-P, Dufrêne YF, et al. Distinct and specific role of NlpC/P60 endopeptidases LytA and LytB in cell elongation and division of Lactobacillus plantarum. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:713. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

189.Delcour J, Ferain T, Deghorain M, Palumbo E, Hols P. The biosynthesis and functionality of the cell-wall of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:159–84. doi: 10.1023/A:1002089722581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

190.Chapot-Chartier M-P, Kulakauskas S. Cell wall structure and function in lactic acid bacteria. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13:9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-13-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

191.Liu Y, Perez J, Hammer LA, Gallagher HC, De Jesus M, Egilmez NK, et al. Intravaginal administration of interleukin 12 during genital gonococcal infection in mice induces immunity to heterologous strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. mSphere. 2018;3:e00421-17. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00421-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

192.Shida K, Kiyoshima-Shibata J, Kaji R, Nagaoka M, Nanno M. Peptidoglycan from lactobacilli inhibits interleukin-12 production by macrophages induced by Lactobacillus casei through Toll-like receptor 2-dependent and independent mechanisms. Immunology. 2009;128:e858-69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

193.Choi S-H, Lee S-H, Kim MG, Lee HJ, Kim G-B. Lactobacillus plantarum CAU1055 ameliorates inflammation in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW264.7 cells and a dextran sulfate sodium–induced colitis animal model. J Dairy Sci. 2019;102:6718–25. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-16197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

194.Wu Z, Pan D-d, Guo Y, Zeng X. Structure and anti-inflammatory capacity of peptidoglycan from Lactobacillus acidophilus in RAW-264.7 cells. Carbohydr Polym. 2013;96:466–73. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

195.Song J, Lang F, Zhao N, Guo Y, Zhang H. Vaginal lactobacilli induce differentiation of monocytic precursors toward Langerhans-like cells: in vitro evidence. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2437. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]